* Gum/breath mints (Most onsite CART jobs involve sitting next to the client. Make sure your breath is fresh! My favorite gum for this purpose is Ice Breakers Ice Cubes, because I love popping the tiny liquid mint bubbles with my teeth.)

* Screen cleaning kit (I used to carry a pen-sized bottle of screen cleaner, but these days I find it's more convenient to use the pre-moistened cloths from Staples, which pack flat and have no danger of leaking. Having a clean laptop -- especially your screen -- is a subtle but vital aspect of professionalism when providing onsite CART. You don't want your client to have to squint through the grime to read your captions, and you don't want them to get grossed out when you hand them a tablet to carry. I also have several cans of canned air, which I keep in my home office, and I try to spray the crumbs out of my computers on a regular basis, but those are too bulky to carry on the job. Single-use screen cleaning cloths work just fine.)

* External battery for phone (I don't know about you, but my Motorola Droid 4 barely holds a charge past noon, no matter how sparingly I use it. Admittedly, that might be because I often get up at 5:30, but still; if I don't get home until 8:00 or so, that's eight hours without a phone unless I find some way to charge it. Typically I'll just plug it into my Surface Pro's auxiliary charger slot. But if for whatever reason I don't have the opportunity to connect it to AC power, this little external battery is there to save my bacon. I can plug my phone into it and leave it in my pocket. It takes an hour or so to charge it back up to full capacity (longer if I'm using it while it charges), and usually has enough juice for about 1.5 full charge cycles. I love it so much I'm thinking of buying another one just to have on hand. They can be pricey, but they're ridiculously useful when you can't get to an outlet, you don't want to drain the power on your laptops (or inconvenience your client) by plugging your phone into their USB slots, and suddenly going incommunicado is not an option.)

* Flat spool of gaffers tape (This is one of my easiest hacks: A length of plastic shelf divider snapped off so it's about 6x4 inches, with a few hundred lengths of gaffers tape wrapped around it. This way, I don't have to bring the huge, bulky spool the gaffers tape comes on, but I always have 30 or 40 feet of it at the ready. Gaffers tape is special because it doesn't leave behind adhesive residue on floors or carpet, and it's easy to tear off pieces either transversely or along its length. I use it to cover over extension cords when my laptop is placed at a distance from an outlet, so that I don't create a tripping hazard. I also use it to cover the indicator lights of my laptop when I'm in a theater or other situation where light leakage would be distracting.)

* ID card on retractable cord (The building I work at requires me to flash my official Contractor badge when I come in, so I hooked a retractable badge holder in to the breast pocket of my ScottEVest jacket, which has a special loop just for the purpose. This way I just have to unzip the pocket, reach in for the card, show it to the guy at the security desk, and then let it go; it'll spool back into my pocket and I can go on my way. Very convenient.)

* Business card case (I have a slim leather one, with my business card on one side and Plover stickers on the other)

* Towel tablets (As Douglas Adams so rightly pointed out, a towel is a ridiculously useful object, especially when you own a lot of expensive electronics. I keep a few lightload towel tablets on hand in case of rain, spills, puddles, wet subway seats, or anything else I might encounter. Extremely useful little objects!)

* Water bottle (I'm extremely happy with my insulated Kleen Kanteen. It keeps stuff cold for hours and hours, and it's got a nice big plastic loop in the lid. I made a length of Velcro tape with the hooks on one side and the loops on the other and ran it through one of the straps on the side of my backpack. Now I have to do is run it through the water bottle's lid and close it on itself, and I know that the bottle will stay in my backpack's mesh side pocket no matter how much bumping and jostling I put it through.)

* Multitool (I love my Leatherman Sidekick, though I admit that frequently I have to take it out of my backpack when I know I have to go through a metal detector or security checkpoint of some kind, and sometimes I forget to put it back in. Still a tremendously useful thing to keep around.)

* Superglue (Individual use tubes of Superglue can be absolute lifesavers when you need to do last-minute repairs to a steno machine that's been knocked to the floor by a careless student. Oh, yes, that's happened to me. More than once. Not fun.)

* 3-to-2 prong adapter (Use these sparingly; I understand that if you don't actually screw the metal bit in, they're not completely safe. But sometimes there just isn't a three-prong wall outlet anywhere, so these can mean the difference between running on battery and possibly going dark during a job or being able to plug in. I always make sure to keep a surge protector between the outlet and my electronic gear, and so far I haven't had any problems at all using this thing, but as with any electrical improvisations, be careful.)

* 1 foot extension cord (More common even than a two-prong outlet is a situation where I just can't fit my surge protector in the available outlet no matter how I twist and turn it. This short extension cord is much more convenient than my usual 15-foot-long one when the problem is just finding space around the outlet to plug in my stuff.)

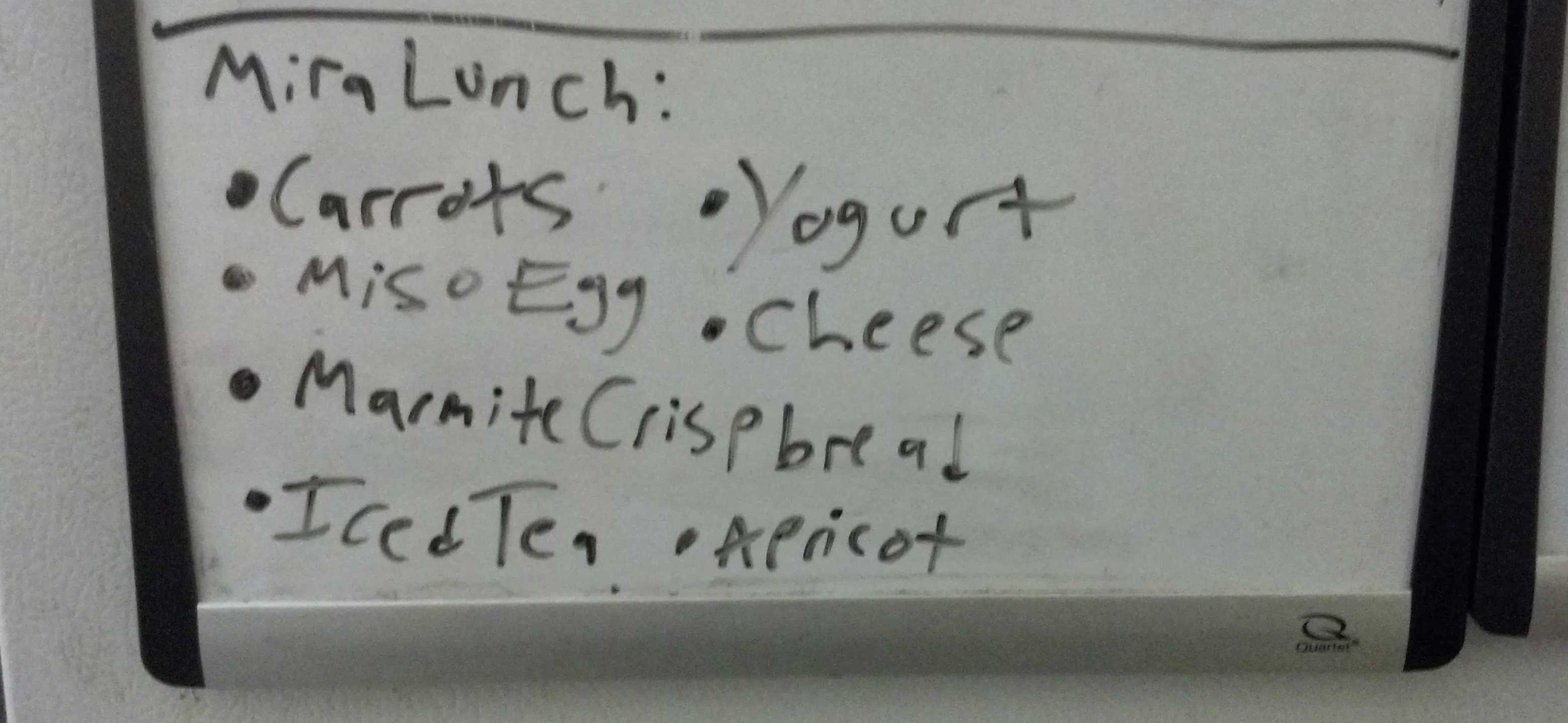

* Sistema cutlery set (not to be confused with Systema, the scary Soviet martial arts technique. My lovely Ladybug Spork broke off one of its wings a few weeks ago, which of course was heartbreaking, but I have to admit that the Sistema Cutlery Set is actually way better. It takes up just a little more space in my bag, but it lets me assemble a full-sized spoon, fork, knife, and chopsticks to suit the needs of any meal. I really like it. I've also started using a Muji bento box, which fits in my backpack's other mesh side pocket, to supplement the stuff I carry in my lunch bag every day. It works really well, and holds more food than the small Tupperware containers I was using before.)

Many thanks to everyone who contributed to this post on Depoman. Below is a selection of things they carry in their bags. Click through to the post for more, especially for court reporting-specific items (about which I know next to nothing. Is an exhibit sticker the same thing as an exhibit label? I have no idea!)

* campus map (for onsite CART)

* cough drops (for scratchy throats)

* Fingerless gloves (for chilly mornings)

* Garbage bags (for putting over steno bag if it rains)

* Kleenex (for spills, runny noses, or emotional witnesses)

* Colgate Wisp toothbrushes (when you have garlic bread for lunch)

* Magnifying glass/whistle/compass (For... Um... I got nothing. Is this another court reporting thing?)

So that's all the non-steno stuff I keep in my bag. Have I left anything out? What bits, bobs, and gewgaws do you bring with you to every job?